Wild Donkeys

I can love a person without knowing their history but I cannot understand a person unless I know their past. I have a few friends who have been created not only from blood but also from earth. They are as much the product of the places they love as they are of those people who love them. Sometimes, in visiting their past, I better understand their present.

We drove together, a friend and I, to a place that has shaped his adult years. It is hard country, a land where nature has rubbed the skin from the earth and its bones stick through. It is far from anywhere. The roads are rough, where they exist. Most were forced through the desert decades ago by men in search of uranium. In places abandoned shafts stare down from imposing peaks and rocky crags like sad, unseeing eyes. Those who dug them mostly left the land broken men, with shattered dreams and the seeds of premature death growing malignantly in their lungs. But this place was a man-killer long before the uranium boom. The old Spanish Trail from Santa Fe to the Pacific Ocean makes an improbably long arc northward through the area, so as to avoid the Grand Canyon and the deadly heat of the Sonoran deserts to its south. As harsh as this place is, it was the lesser of two evils. And nature forced each traveler to pay a toll for taking this easier way, often in their own blood.

Wild horses roam here. Over the centuries their ancestors were abandoned by their owners, scattered during raids, or lost through negligence. The strongest survived and today their grandchildren wander an area nearly the size of Delaware, perpetually in search of water and food but free. A few donkeys also remain, burros as the Spanish called them. They number in the dozens. Smaller and slower than horses they are easier prey for mountain lions and coyotes. And yet they live, doughty, determined, too obstinate to yield, persisting in a place too hot in the summer, too cold in the winter, too dry the year round, in a country seemingly inimical to life itself.

Neither of us had seen a wild burro since the last days of Nixon’s presidency. They are scarce, skittish and scattered. But as we rounded a bend in the road we unexpectedly happened upon a herd of seven, partially hidden in a rock-strewn ravine a few hundred yards away. They browsed on sparse dry brush, their ears erect, keeping a very careful eye on us. We stopped, astonished, fascinated, and quietly watched. Our presence obviously made them uneasy so we left reluctantly, all too soon. But as we rounded the very next corner we found three more burros warily grazing a stone’s throw from the road. Again we stopped and silently watched. We could see the animals easily, clearly. They were well-fed and healthy in spite of the place they live. And again, finally, having disrupted their feeding, we felt compelled to leave before we were ready.

We could not help but discuss them as we drove through the darkness, homeward. Asses are always described derisively, referred to pejoratively. Perhaps these desert donkeys, these survivors, deserve better.

Skim A little Off the Top–The Black Skimmer

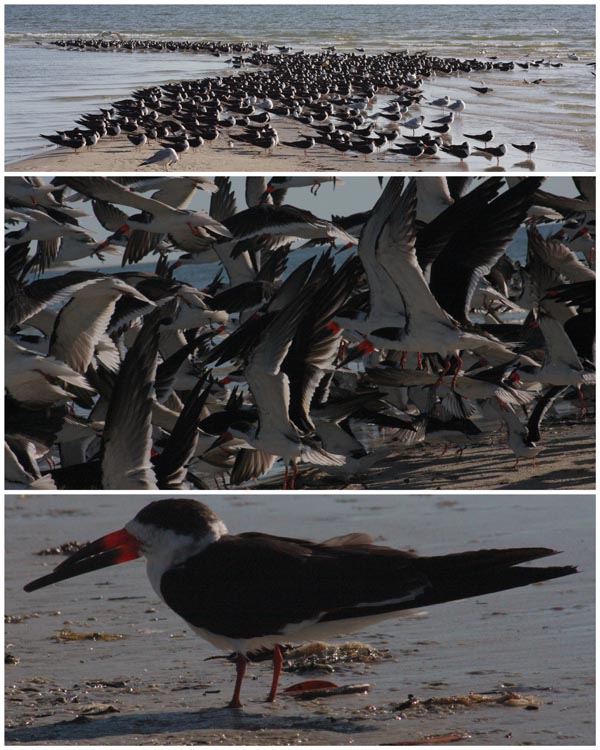

The bill of a bird often says a lot about how a bird feeds and what they feed on. If you’d never seen a Black Skimmer (Rynchops niger) before you could certainly tell they have a unique beak. The upper mandible is considerably shorter than the lower mandible. They don’t sift their food like a spoonbill. They don’t probe the mud and worm holes like an ibis. They don’t tear their food like a hawk.

Just as their name would suggest, they skim for their food. Flying low over the water, the skimmer places the lower mandible beneath the surface and continues to fly until it feels something touch the bill – and then snaps the bill shut. Amazingly, when the skimmer catches fish or other prey species, the head drops into the water and points to the tail end of the bird. The bird maintains flight, lifts the head back out of the water continues the hunt.

The lower bill of the Black Skimmer is constantly growing to combat wear from friction as the bird skims the surface of the water. The upper mandible does not grow at the same rate, resulting in an asymmetrical appearance. The difference in length of each mandible makes picking up objects with the bill more difficult. The upper and lower bills of juveniles are roughly the same until the bird matures.

The eyes of the skimmer are largely ignored by casual birders as they’re relatively small compared to the stout size of the rest of the bird. The eye has a pupil similar to that of a cat or an alligator and can be closed to a vertical slit. This type of eye is best for night foraging.

This flock of about 200-250 Black Skimmers was located on Bunch Beach in Fort Myers. The somewhat secluded sandbar is a preferred resting spot for skimmers, godwits, turnstones and other shorebirds. As I paused to take a photo, a jogger detoured towards the birds. Oddly, the skimmers took flight while other species remained. After a moment, the skimmers circled back and rested again on the sandbar.

Mother Black Bear

Location: Sugarbush, VT

I seem to be on a bear roll lately, this time about American black bears (Ursus americanus), the smallest and most widespread of North American bears, though often weighing 500 pounds or more, they aren’t exactly petite.

Last week, I hosted a women’s ski camp at Sugarbush, Vermont. The ski area spans several peaks along a high ridge of the Green Mountains. The area between Lincoln Peak and Mount Ellen is well-documented black bear habitat, so there is a keen interest in black bears at the resort. As the women in the camp gathered on the first morning, a member of the resort’s staff unaffiliated with the camp burst into the room. She pointed excitedly her laptop.

“Look at the bears!” she exclaimed, “You can see the babies!” Her laptop showed streaming video from a bear-cam that had been placed in a den (www.bears.org). The mother bear had both a yearling cub and twin newborns. Apparently, Mama Bear had mated successfully again though most female bears don’t give birth while nursing a cub. Interestingly, the yearling, named Hope, is proving to be a caring big sister who “helps” her mother with the infants as much as a hibernating bear can actively participate in any activity.

Though a hibernating bear is not deeply asleep, its metabolism slows way down. For three to five months of winter, they do not eat, drink, urinate or defecate. Females give birth in late January or early February during hibernation, typically to two cubs that weigh about 10 ounces each and are only about eight inches long. Cubs nurse for up to 18 months, which means Hope is likely nursing beside the newborns.

I’ve only seen one wild black bear. It was two summers ago while paddling on a multi-day canoe trip on the Smith River in Montana. An immature bear was playing in a shallow part of the river. He took one look at our canoe, sprinted from the water then bolted up a tree. I’m not sure who was more wary and nervous, him or me, but at least I calmed down enough to get a photo of him.

Hoary Redpolls

If we haven’t crossed paths for a while, Syl, a longtime friend of mine, almost always asks me if I’ve seen any Rosy-breasted Pushovers lately. This is a typical non-birder to birder joke; birds with “funny” names often provoke snickers and bad jokes. Once when I told him I’d just seen a rare Hoary Redpoll, his reply was: “Whoring Red Poles? There are actual birds with that name? That’s obscene!”

Well, they’re not obscene; in fact they’re not even seen all that often – at least not in my neck of the woods (Manitoba). If there are redpolls around, and they usually show up sometime during the winter, the first thing I do is check for Hoaries. It’s a knee-jerk reaction. Any Hoares in that flock? If I’m lucky, I’ll get one or two or three Hoaries per winter. I’d say that over ninety-five percent of the Redpolls here are Commons.

For some reason, this year it’s different. Like many of my birding friends, I’ve been amazed to find that the Hoaries outnumber the Commons this year. In the one flock of fifty or so that I encountered, the usual percentage was completely reversed. I was hard-pressed to spot a Common Redpoll in the bunch! In Marathon, Ontario (relatively nearby, north of the Great Lakes), Michael Butler reports the same phenomenon: Percentage wise, at least 70% Hoary to 30% Common.

What this has done is make me a more observant birder. If in an average winter you only see one or two of these little puffs of white with the jaunty red cap tilted forward, you’re happy to just say “Hoary”. You take them all for granted when you shouldn’t. But if you see fifty, you start to look for variations.

In fact, there are two subspecies of Hoary Redpolls. I guess in years past I saw examples of Carduelis hornemanni exilipes, the expected subspecies of the area. This year people have been seeing the bigger and paler version as well – the Carduelis hornemanni hornemanni. I think I may have seen one as well. But the flock was so jumpy that they flitted off from the birch tree they were in before I could get a fully positive read.

I’m participating in what’s turning into an irruption year for Hoary Redpolls. (That sounds even more obscene, Syl!)

What the Hidden Eye Sees

Some good friends of ours recently bought a piece of property in the nearby Sulphur Springs Valley. They live in Minnesota and visit occasionally but asked me to keep an eye on the place and begin some simple restoration to a habitat that shows signs of past abuse. Most of the native grasses are gone and the remaining mesquite is the dominant plant species. In some areas the topsoil has been eroded and so I began constructing small check dams to slow the sheet erosion. I have to admit, even to a confirmed Desert Rat, the place looks pretty bleak.

But we had seen tracks along several of the washes that traverse the property and I decided as part of my monitoring, I would install a couple of motion sensitive cameras to see what was moving when I was not visiting. The results were surprising. Every week I would check the cameras and bring home the chip that stores the images for a glimpse into the unseen world on this patch of desert. I will admit I also left a little cat food as an enticement to any passing predator to stick around long enough to have its picture taken. In just a few weeks I had assembled an album of residents and visitors that include the neighbor’s dogs, several coyotes (one photo had three Coyotes in view), Grey Fox, Hooded Skunk, Black-tailed Jackrabbits, Desert Cottontails, Javelina, Mule Deer, Ord’s Kangaroo Rat and the real prize, a nice Bobcat. We even caught an image of the bobcat returning from a hunt dragging a jackrabbit. A small water basin and some birdseed brought a variety of birds from Black-throated Sparrow to Red-tailed hawk, Chihuahuan Raven and a Greater Roadrunner.

Most of the activity is at night, although the javelinas have become regular daytime visitors to the water basin. I’ve enjoyed the opportunity to remotely monitor the activity on this property and the diversity present makes me even more pleased to be a part of its restoration. Now I know there are many residents awaiting our improvements.

The Paradox of Winter Precipitation

Snow is piling up in northeastern Montana. Two to four feet of packed ice crystals cover the prairie. Deer and antelope are dying by the hundreds, many from starvation. The animals simply expend too much energy pawing through the crusted drifts in relation to the bits of fodder they uncover on the frozen ground below. Seeking sanctuary from the endless miles of deep snow through which they flounder in single file, vast herds of antelope congregate on the railroad tracks snaking across the prairie. The Montana Department of Fish, Wildlife and Parks recently reported that over 200 antelope were killed near the lonely outpost of Hinsdale. The carnage was strewn for over a mile along the tracks.

Although the potentially record-breaking snowpack is decimating some species, it will likely prove a boon for others. The northeastern corner of the Treasure State is a portion of the country known for its prairie potholes, wetlands and small ponds essential for the nesting and reproduction of numerous species of waterfowl and other wetland-loving birds such as American avocets and black-necked stilts. Come spring, the water left behind from the melting snowpack will provides superb nesting conditions for these birds.

Such is the paradox of winter precipitation. Too much of it creates dismal and deathly environmental conditions for ungulates, but benefits the magpies, coyotes, bald eagles and other scavengers that feed upon their carcasses. Too little snowfall means easy wintering for ungulates, but lower water levels in the spring shrink wetlands, constricting habitat for birds. A “happy medium” is the best for both worlds — but in the harsh climate of northeastern Montana, Mother Nature seems to prefer her extremes.

Ugly Baby–The Wood Stork

It’s generally considered bad behavior to scream at birds and yet there I was flailing my arms and yelling at an endangered Wood Stork (Mycteria americana) who was gracefully flying near my home. Everyone knows that the White Stork (Ciconia ciconia) brings babies and pickles, but the bald, black-headed, wrinkle-skinned Wood Stork brings ugly babies and my wife was due in two weeks.

The Wood Stork is an opportunistic nester. Too little water and their diet of fish, frogs and invertebrates may dry up. Too much water and the same dietary cast of characters can easily disperse, making it tough to for nesting parents to capture enough food to feed themselves, let alone their young. To raise two chicks they require nearly 450 pounds of food throughout the nesting season. If they can’t find food, they don’t nest and if the season goes sour they may abandon a nest.

In the air they are remarkably elegant, using long, broad wings to soar on thermal updrafts and swoop in to marshes and swamps. On approach they drop down their landing gear, a pair of thin, sturdy legs that reminds me of the wheels on a plane. Up close they have a face that looks like a vulture. Although younger storks retain a slightly feathered head, “stork-patterned baldness” sets in upon adulthood, providing an easier feeding experience as they dunk their smooth, domed heads in the water to seek prey.

I love Wood Storks. I can’t help but point one out every time I see one. I’m just superstitious and on this particular day as the white and black bird glides over the pines and nears my lawn, my soon-to-be parent instinct leads to my maniacal “nooooooooooooooooooooooo”. It works and the bird majestically takes a slightly altered flight line.

Theodoro Corradino was born on 1/31/2011. If he’s anything but the most beautiful baby I wouldn’t know. I would imagine the Wood Storks think the same of their hatchlings.

Of Fruit and Flowers

These are the dog days of summer…in the southern hemisphere. We need a winter equivalent here to signify these short, cold, and above all, very gray days as the calendar flips from January to February.

One thing that characterizes these mid-winter days for me is that monochromatic tedium of gray: gray branches etched against gray skies. At this point, birds have stripped away the fruit from dogwoods, cedars, hawthorns, and crabapples. Even the fruit of introduced plants such as honeysuckles, buckthorns, and Asiatic bittersweet – so abundant in urban areas – is for the most part long gone.

Just about the only splash of vegetative color is the red hanging clusters of fruit from the highbush cranberry, Viburnum opulus. (The taxonomy is a little tortured – V. opulus is the introduced European shrub, while the native variety is sometimes known as V. trilobum. They’re now usually considered subspecies; in much of the northeast you might find one, the other, or hybrids.) Although it gets picked at occasionally by birds after it ripens in fall, most highbush cranberry fruit isn’t consumed by birds until early spring.

I had always heard the fruit on highbush cranberry remains all winter because it didn’t “taste good” to birds until it had frozen and thawed multiple times. In fact, studies with captive American Robins and Cedar Waxwings determined that they preferred fall fruit in side-by-side trials. Sugars in highbush cranberry fruit do concentrate over the winter due to dehydration, but the chemical composition remains the same, and songbirds, in any case, don’t have much of a sense of taste.

The real reason birds don’t eat highbush cranberry fruit until spring is a little more complicated. The fruits are very acid and low in nitrogen. Birds need a supplemental source of protein to properly metabolize highbush cranberry fruits. In early spring, this protein source is often pollen, in the form of the insignificant-looking flowers of trees like cottonwoods, maples, and oaks.

This is a pretty clever strategy on the part of the Viburnum. In the fall when the fruit ripens, there is a whole smorgasbord of other fruit for birds to choose from. By retaining fruit until spring, highbush cranberry reduces the competition, and hones in on a very efficient seed disperser: the Cedar Waxwing (or in Europe, Bohemian Waxwing). In spring, at a time when many other bird species are beginning to rely on insects for food, waxwings remain mostly dependent on fruit, and highbush cranberry has set the table.

When a flock descends on a patch of highbush cranberry shrubs and goes to town on the fruit, you might also note that they make frequent forays into neighboring trees to partake in a little meal of pollen, completing their dietary requirement. As is their habit, waxwings wipe out a patch of berries and then go on their nomadic way, distributing Viburnum seeds far and wide, just as nature planned it.

Winter Forage for Wild Turkeys

Location: Hanover, NH

There’s something incongruous about a 20-pound bird sitting in a tree with branches barely fatter than twigs, but that’s exactly where I found this Eastern wild turkey (Meleagris gallopavo silvestris). She was obviously after the red berries that covered this young ash. A dozen of her friends strutted on the ground under her, jauntily pecking at the red raindrops that fell every time she moved. About 90% of a wild turkey’s diet is plant matter. During the winter, they often feed on the fruit that hangs on the longest, not only ash berries, but also barberry, rose hips and apples.

It’s so nice to see wild turkeys in such abundance again! When I was a kid, they were as rare as the Northern Lights on an overcast night. In fact, they had totally disappeared from New Hampshire about 150 years ago due to loss of habitat and unregulated hunting. Today, about 25,000 wild turkeys forage for berries, bugs and seeds in the Granite State, thanks to a relocation effort that began in the 1970s.

Turkeys can run up to 20 miles per hour and fly twice that speed, yet the one in this picture was happy to munch on berries as she watched me with a wary eye, at least for a short while. She soon hopped down to the ground then followed her friends under a fence and into the woods. It was remarkable how so many large birds could instantly disappear. Interestingly, by spring, this flock will likely disperse as the hens, toms (mature males) and jakes (young males) don’t mix during the mating season. One dominant tom gets all the girls.